You’ve probably heard people use the terms geomancy feng shui as if they mean the same thing – but do they really? While both deal with energy and the earth, they come from very different traditions. Feng shui, which means “wind-water” in Chinese, is all about arranging spaces to create harmony and attract good fortune. Geomancy, on the other hand, began as a Western method of divination—reading patterns in the earth to predict the future.

In Singapore, it’s common to hear feng shui consultants referred to as “geomancers,” which adds to the confusion. So in this article, we’ll break down what each one really is, how they differ, and why the mix-up happens – especially in the local context. If you’ve ever wondered how geomancy and feng shui actually compare, this guide is for you.

What is Geomancy?

Definition of Geomancy

Geomancy literally means “divination by earth”. Its roots lie in medieval Arabic and Greek traditions. The Arabic name was ʿilm al-raml (“science of the sand”) or Khatt al-raml (“lines in the sand”).

Practitioners would cast random dots in soil or on paper and group them into sixteen geomantic figures. Each figure (with names like Fortuna Major, Tristitia, etc.) had a symbolic meaning.

The full set of figures – often called the geomantic tableau – was then interpreted to answer questions. In effect, geomancy was a kind of divinatory Q&A system rather than an architectural science.

In short, feng shui masters view a well-arranged space as one where qi can circulate freely, yin and yang are balanced, and the five elements are represented. This approach is meant to help people feel calm and supported by their environment.

History and Practice of Geomancy

Western geomancy flourished in the Middle Ages. Geomancy manuals were widely written in Arabic and Latin. (Christian authorities often forbade it as one of the “forbidden arts”.) The practice was systematic: after generating the figures, a geomancer would “look up” the answer in extensive tables of predictions. For example, 17th-century geomancy books contain pages and pages of outcomes for questions about money, travel, health, love, war and so on. Once the dot figures were drawn, the answer was read from these charts. As one 17th-century source explains, geomancy became “long tables answering all sorts of questions about money, love life, war, children…”. In short, geomancy gave straightforward yes/no or predictive answers from a predefined list.

In practice, geomancy is very different from Feng Shui. Western geomancers viewed the earth itself as a mystical medium. They might use simple tools – a stick to mark dots in sand or holes – but no complex instruments. (Some later geomancers even used dowsing rods or pendulums to generate figures.) There is no concept of qi or building layout in classical geomancy. Instead, it treats the patterns in earth or sand as omens to be interpreted. Modern “earth-energy geomancy” (often involving water-dowsing and earth-healing) has emerged, but this is a new evolution. Traditional geomancy itself (the dot method) is now mostly of historical or occult interest.

What is Feng Shui?

Meaning and Core Principles

Feng Shui (风水), by contrast, is a Chinese system for arranging spaces. The words literally mean “wind” and “water”, reflecting the idea of qi flowing like breeze or stream. It is often called “Chinese geomancy” in English, but that label is misleading. Feng Shui is about harmonising humans with their surroundings. The Singapore National Library Board explains that Feng Shui is “a study of man’s position in the environment,” blending astrology, geography, architecture and even psychology. In practice, Feng Shui consultants consider many factors – compass direction, shape of land, building orientation, colour, and decor – to balance the flow of qi (气, life energy). Good Feng Shui might mean positioning a house so that a protective hill stands behind it and a waterway (or road) runs in front. The goal is to channel auspicious energy into living and working spaces, improving luck, health and prosperity.

Feng Shui theory also uses the Five Elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) and Yin–Yang balance. For example, each direction in the Luo Pan compass or Bagua map corresponds to an element and an energy type. Practitioners may place objects (like water features, mirrors, plants, or wind chimes) in certain “wealth” or “health” areas of a home to enhance beneficial qi. Notably, Feng Shui is not a system for foretelling the future. It is a practical design and placement art. As one scholar emphasizes, “feng shui is concerned with changing luck, rather than predicting the future”. In other words, Feng Shui tries to improve your present situation by design – it doesn’t try to give you specific predictions.

History of Feng Shui

Feng Shui has ancient Chinese roots, going back over two thousand years. Early dynasties (Shang, Zhou) selected tombs and capitals based on auspicious orientation. By the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE), Feng Shui was a formal discipline taught by masters like Yang Yunsong (nicknamed the “Saviour of the Poor” for teaching it broadly). Over centuries, Chinese cities, palaces and villages were routinely laid out using Feng Shui rules: for instance, planners often aligned streets and buildings to face southward, and chose burial mounds with favorable landforms. Even the layout of the Forbidden City and imperial tombs followed Feng Shui principles. In modern times Feng Shui has experienced revivals, but the key ideas remain those of classical China: aligning design with nature to enhance the occupants’ fortunes.

Practice of Feng Shui

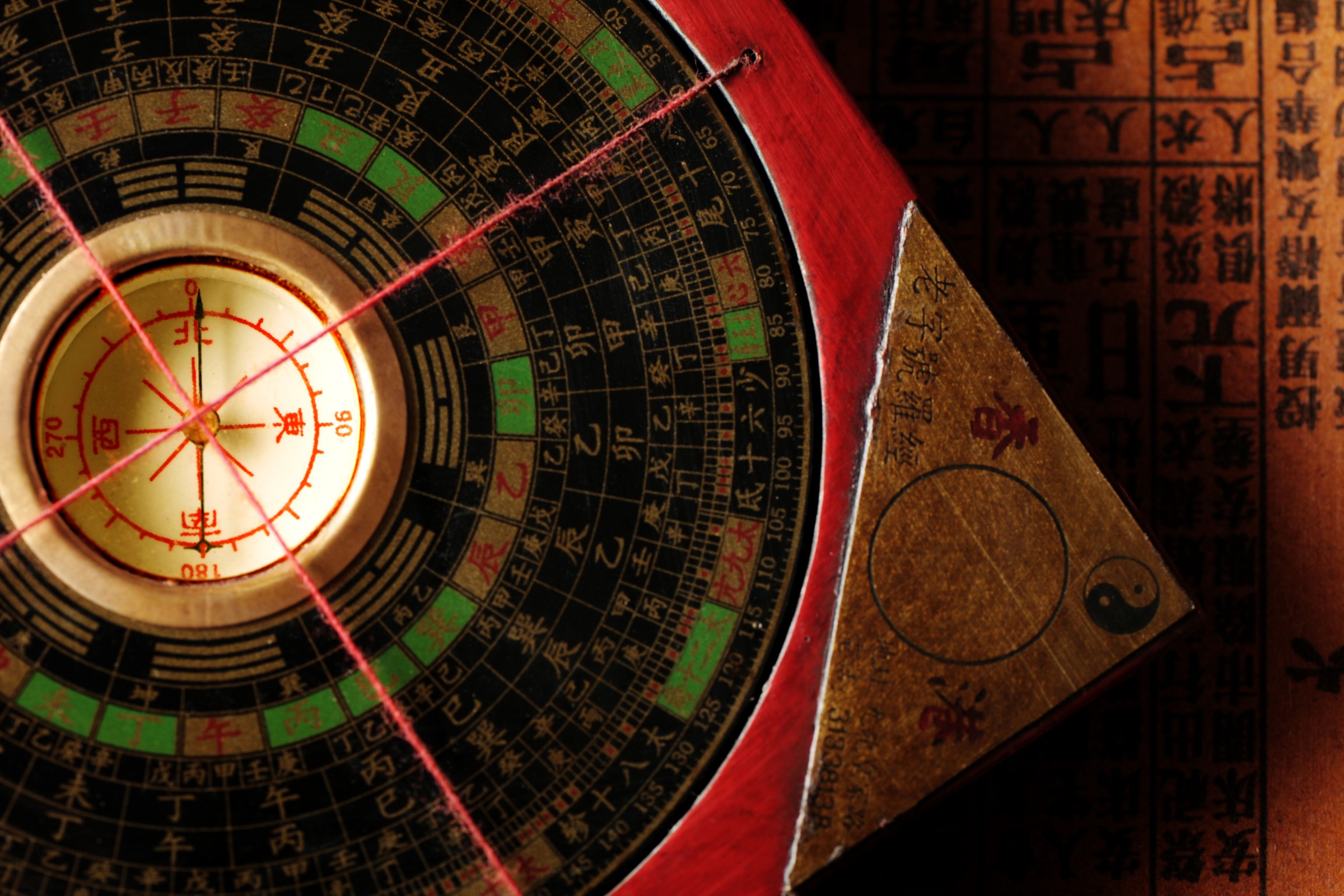

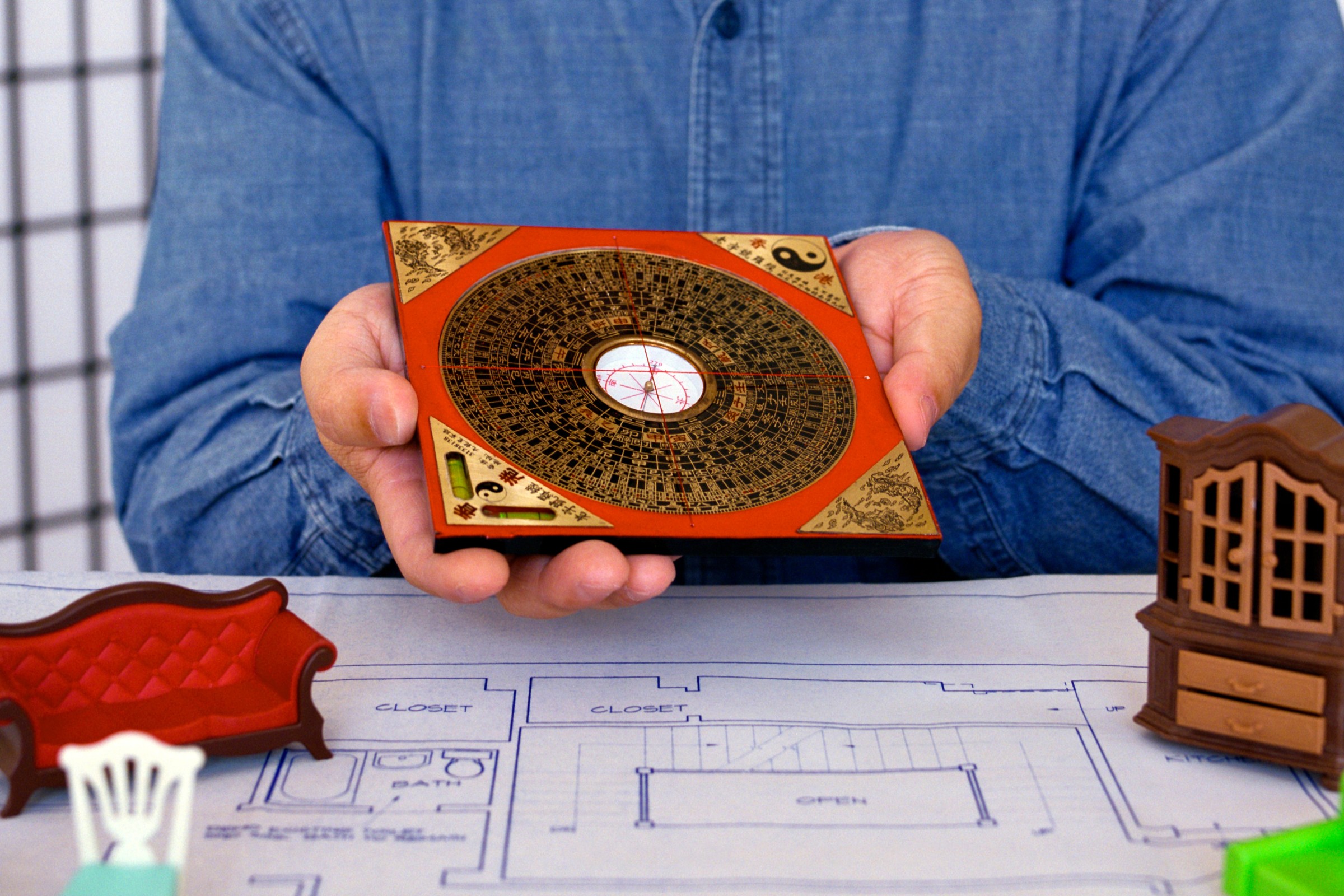

A typical Feng Shui consultant today uses a mix of science and intuition. They carry a Luo Pan (feng shui compass) and use almanac charts or Bagua (eight-trigram) overlays. On site, they “sense” the space’s energy flow. They might identify a blocked “dragon vein” (qi line) under a building or detect imbalance by how air flows. Remedies are usually concrete: move a bed or desk, add a fountain or salt water cure, place coins or crystals in a corner, etc. These actions are meant to enhance the good qi and mitigate any “sha qi” (negative energy). Importantly, Feng Shui adjustments are pragmatic: putting a mirror or plant in a certain spot is not a mystical ritual, but a way to symbolically correct an energy pathway.

In Chinese tradition, Feng Shui also involved choosing lucky dates and names. For example, building permits or apartment openings might be delayed until an auspicious day on the lunar calendar. Naming a baby or business in harmony with elemental cycles is another Feng Shui practice. In short, Feng Shui pervades many aspects of life. But whether it’s layout or timing, the common theme is arranging in tune with cosmic and earthly patterns to promote harmony.

Geomancy vs. Feng Shui: A Comparison

Key Differences

Similarities and Misconceptions

Superficially, both systems treat the earth as important. Feng Shui’s Form School explicitly studies the shape of hills and rivers. As one Feng Shui scholar notes, “‘Geo’ as in earth is correct when we define Form School or Landscape School”. In other words, Feng Shui does pay attention to landforms, just as Western geomancers noted mountains or watercourses. Both believe nature affects human fortune. However, this overlap is mainly conceptual. The way each uses land is very different: Feng Shui looks at terrain to balance energy (for well-being), whereas geomancy turned terrain into symbolic signs (for predicting events).

Another point: critics classify both Feng Shui and geomancy as pseudoscience. Neither has experimental proof, so scientists dismiss them as beliefs. But culturally, people still consult them. In Singapore, Feng Shui is treated like a practical advisory service – it’s part of tradition. Western geomancy, by contrast, isn’t part of Singapore culture at all. This leads to confusion: many Singaporeans speak of “geomancers” and think of Feng Shui experts, not diviners of dots.

An important modern distinction: Western-style geomancy has branched into “earth healing” practices with dowsing and energy grids. Modern geomancers in Europe or America may use water dowsing rods or earth-acupuncture to cure geopathic stress. These methods simply do not exist in classic Chinese Feng Shui. In Singapore, if a “geomancer” pulls out a bagua chart or a Luo Pan compass, that’s Feng Shui. If someone starts measuring ley lines and inserting metal rods into the ground, they’re in a different tradition altogether.

In summary, the only real common ground is that earth and energy matter in both. But Feng Shui uses that idea in one way (designing for qi), and Western geomancy used it in another (making oracles). Practically speaking, it helps to keep the terms separate: Feng Shui is about auspicious design, while “geomancy” in the original sense was a type of fortune-telling.

Geomancy and Feng Shui in Singapore

Local Usage and Beliefs

Singapore’s Chinese community uses Feng Shui extensively, and the local usage of “geomancy” reflects that. In everyday speech, a Feng Shui consultant is often called a “geomancer”. The Singapore National Library Board explicitly notes an “active community of professional geomancers who practise feng shui”. In practice, this means people consult these experts for housing and offices. Many Singaporeans will get a feng shui blessing or adjustment before moving into a new flat or launching a business. According to Sara Noble’s study, Singaporean “geomancers” are usually hired after a building exists, simply to “correct and enhance” its Feng Shui. However, she also found that savvy developers now involve Feng Shui from the planning stages to gain a “trade secret” advantage.

At the family and personal level, Feng Shui beliefs run deep. For example, Chinese buyers often avoid floor numbers or road addresses with unlucky digits (like 4) and seek out auspicious ones (like 8). It is common for companies to choose auspicious opening dates by consulting a feng shui calendar. Even in schools or clinics, one might find small pagodas or wind chimes hung in corners for balance. These practices show how Feng Shui is woven into daily life in Singapore. By contrast, practices resembling Western geomancy (casting lots in the dirt) are virtually unknown here.

Influence on Architecture and Business

Major Singapore developments have had Feng Shui input. One famous case is Suntec City (built in the 1990s). Feng Shui planners arranged its five towers like a dragon’s hand grasping a pearl (the central fountain). The result was a design that Feng Shui interpreters praise; in fact, the National Library Board cites Suntec City as an example where Feng Shui “influenced the blueprint” of the complex. Similarly, many believe the design of Marina Bay Sands and other skyscrapers was done with Feng Shui advice (for instance, aligning certain floors toward water).

In the business world, Feng Shui is treated almost as a strategic asset. Many Singaporean firms quietly consult Feng Shui masters for office layout, even though they seldom advertise it. Noble notes that companies used Feng Shui at “all phases of development” on projects, as if it were an unspoken competitive edge. Some high-profile Singapore firms have had in-house geomancers. In contrast, Western-style geomancy has no such role here. If a temple, condominium or shopping mall employs a “geomancer,” it’s almost certainly a Feng Shui expert.

Overall, Feng Shui shapes the physical and cultural landscape in Singapore. Its principles influence how buildings are placed, how offices are furnished, and even how companies brand themselves. Western geomancy (dot-divination) has no comparable footprint in Singapore. The term “geomancy” is used locally to mean Feng Shui practice, so understanding the difference is mainly an academic exercise – except to ensure one uses the right tradition.

Final Thoughts

Geomancy and Feng Shui are not the same, despite the confusion in terminology. Western geomancy was originally an Arabic/European divination art (literally “earth divination”). Chinese Feng Shui is an art of placing structures to harmonise qi (literally “wind-water”). The only reason they were ever linked is linguistic accident: 19th-century scholars dubbed feng shui “geomancy” in translation. In practice, their goals and methods diverge. Feng Shui is about changing luck through design, whereas Western geomancy was about predicting the future with earth patterns.

In Singapore and similar contexts, the terms do get blurred. Singapore’s NLB even notes an “active community of professional geomancers who practise feng shui”. But it’s important to interpret that correctly: here, a “geomancer” usually means a Feng Shui consultant, not a practitioner of medieval geomancy. In other words, if someone in Singapore offers “geomancy” services, they almost certainly mean Feng Shui techniques. The old art of casting dots in the sand is a separate tradition, largely of historical interest. Keeping the terms distinct clarifies which practice is being discussed.

Have a question for us?

We welcome any question with no commitments. Master Louis Cheung will seek to clarify any doubts you may have.

“Master Louis Cheung has an approachable and comfortable personality along with competent skills. I can confidently recommend Master Louis Cheung to my friends. Thank you, Feng Shui Master Louis Cheung.”

James H.

James H.Senior Financial Analyst